Fueling a traditional, gas-powered car is easy: drive it to any gas station, where the pump and nozzle will work regardless of the car’s make or model. Fueling an electric car, by comparison, can seem a bit more daunting. Which plug type matches? What charging speed is desired? And what’s a kilowatt, anyway?

Making the switch takes a little familiarization with the terminology related to electric vehicle charging, as well as rethinking traditional fueling patterns. Even the fastest EV charging today is slower than typical gas fueling. On the other hand, EVs can be charged at a wide variety of locations, including by anyone at home without any specialized equipment!

What’s your need for speed?

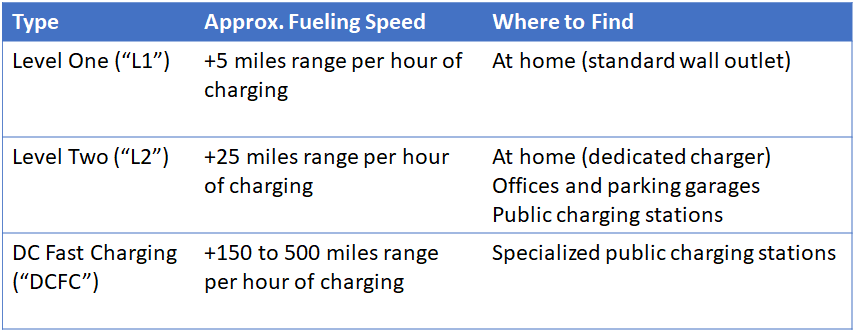

L1 charging

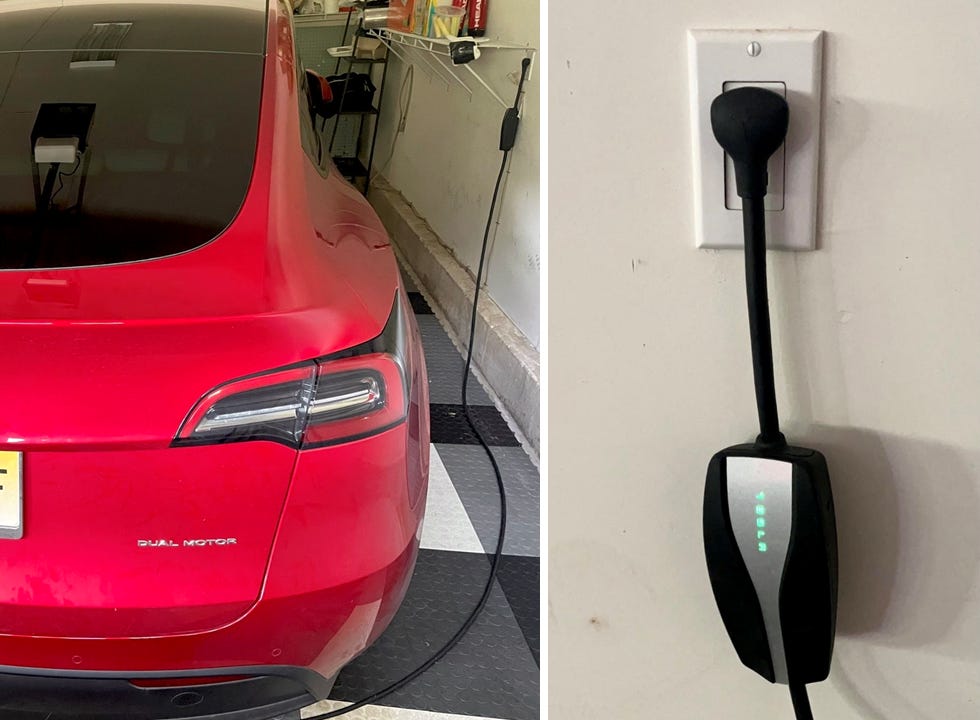

You can charge a big ol’ car on the same type of outlet in which you plug your laptop or blender. It’s slow, but a good solution if you park your EV overnight in a home garage. (Cue Vin Diesel: “I got nothing but time.”) My friend James reports that he adds five miles of range for every hour his Model Y is plugged in. Most days he adds 50-60 miles of range, at a negligible cost, from the time he gets home in the evening until taking the car out the next morning.

Various sources indicate the average daily driven distance in the U.S. is 30-35 miles. For folks with access to home charging, then, the vast majority of their fueling needs are covered without having to go anywhere else!

L2 charging

I’m a city apartment dweller and I have to park my car on the street, so I’m fully dependent on charging away from home. (At least until I try this.) Most of the time I rely on L2, a catch-all bucket of moderate-speed chargers that can include specialized home or office installations, public parking garages, and commercial establishments. (My employer operates a national network of chargers located at grocery stores, malls, movie theaters, etc.)

Were you to charge your car from near-empty to full via L2, it could take several hours. At an average of 25 miles added range per hour, and inexpensive (sometimes offered free as an amenity), L2 charging is far better suited for frequent top-ups. Charging during just the time I’m in the supermarket offsets the driving I do on a light day, while being plugged in for a half-day at the office usually covers my driving for most or all of the workweek.

Some folks choose to install an L2 charger at home. Popular options like the Tesla Wall Connector or the Enel X JuiceBox run $500-$650, plus the cost of installation by an electrician to run on a circuit in the same way as do larger household appliances like a washer or fridge.

DC Fast Charging

Then there are the times you’re driving longer distances, and need to charge your battery in minutes, not hours. Enter DCFC, which uses specialized equipment to provide a lot more electricity (via direct current) than you get from L1 and L2 chargers (which use alternating current).

With DCFC, you’re more likely to notice some quirks that come with managing an EV’s battery. DCFC stations vary widely in how quickly they charge your car; the max “potential” power they offer is denoted by a number of kilowatts. A 350-kW charger (top-of-the-line today) should blow away a 50-kW charger. By how much may depend on how many other cars on site are simultaneously charging, and (particularly for older EV models) what is the highest power output the car accepts.

Charging speed tends to slow down, sometimes significantly, to protect the battery’s long-term health after it has reached 80% charged. Combined with the noticeably higher cost of fast-charging (sometimes, but not always, price-competitive with equivalent gas fueling), I don’t rely on DCFC to fill my whole tank unless I’m on a road trip. Even a 5-10 min pit stop, not much longer than it would take to fill gas, provides a sufficient range boost on most occasions.

The alphabet soup of connectors

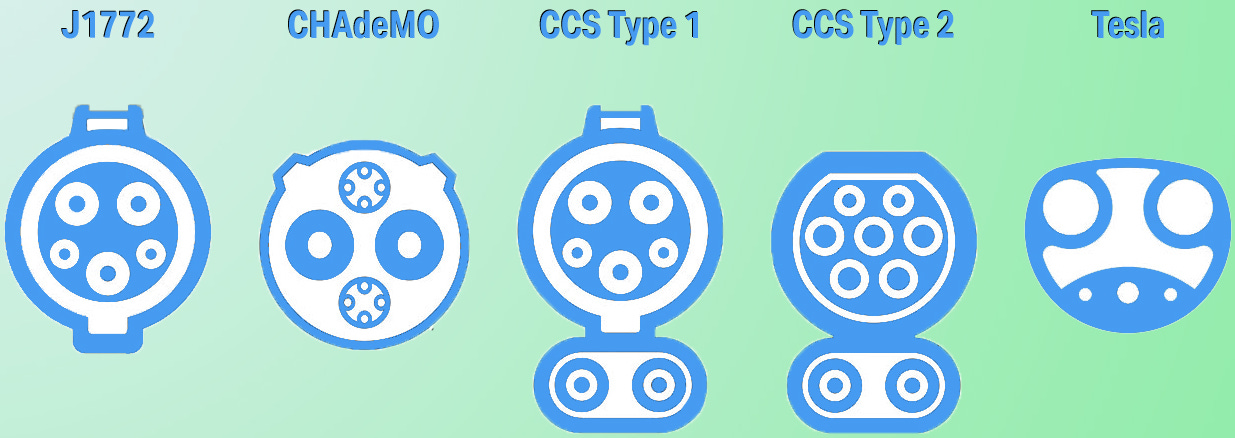

There’s one more piece of the puzzle to sort through, and that’s plug type, or “connector,” for the end that goes into the car. Hey, even iPhones and Android don’t use the same type of charging cable, so it’s disappointing—but unsurprising—there’s not a universal standard for electric vehicles. In the US, different vehicles and charge speeds can warrant different plug types.

Every car can do its L1 and L2 charging via an industry standard connector called the SAE J1772 plug (“J plug,” for short). Tesla, which uses its own proprietary plug, includes an adapter with all its vehicles that also lets its drivers charge seamlessly on this standard.

For fast charging, the older standard is called CHAdeMO. It was popularized by Japanese automakers on vehicles such as the Nissan Leaf. Reminiscent of other famous format wars of the past (VHS/Betamax, Blu-ray/HD-DVD), CHAdeMO went head-to-head versus a newer rival, CCS. The latter was largely favored by American and European automakers. After a decade, Nissan announced their switch to CCS in 2020, paving the way for future consolidation.

In the US, Tesla remains the major holdout to using CCS for fast charging. It may only be a matter of time, though, as in Europe Tesla has already come around to the reigning CCS (“Type 2”) standard there. Until then, this means that only Teslas can fast-charge on its U.S. Supercharger networks. And aside from a recent partnership with EVgo, or without some rare and expensive adapters, Teslas can’t fast-charge on other U.S. public networks.

Juice world

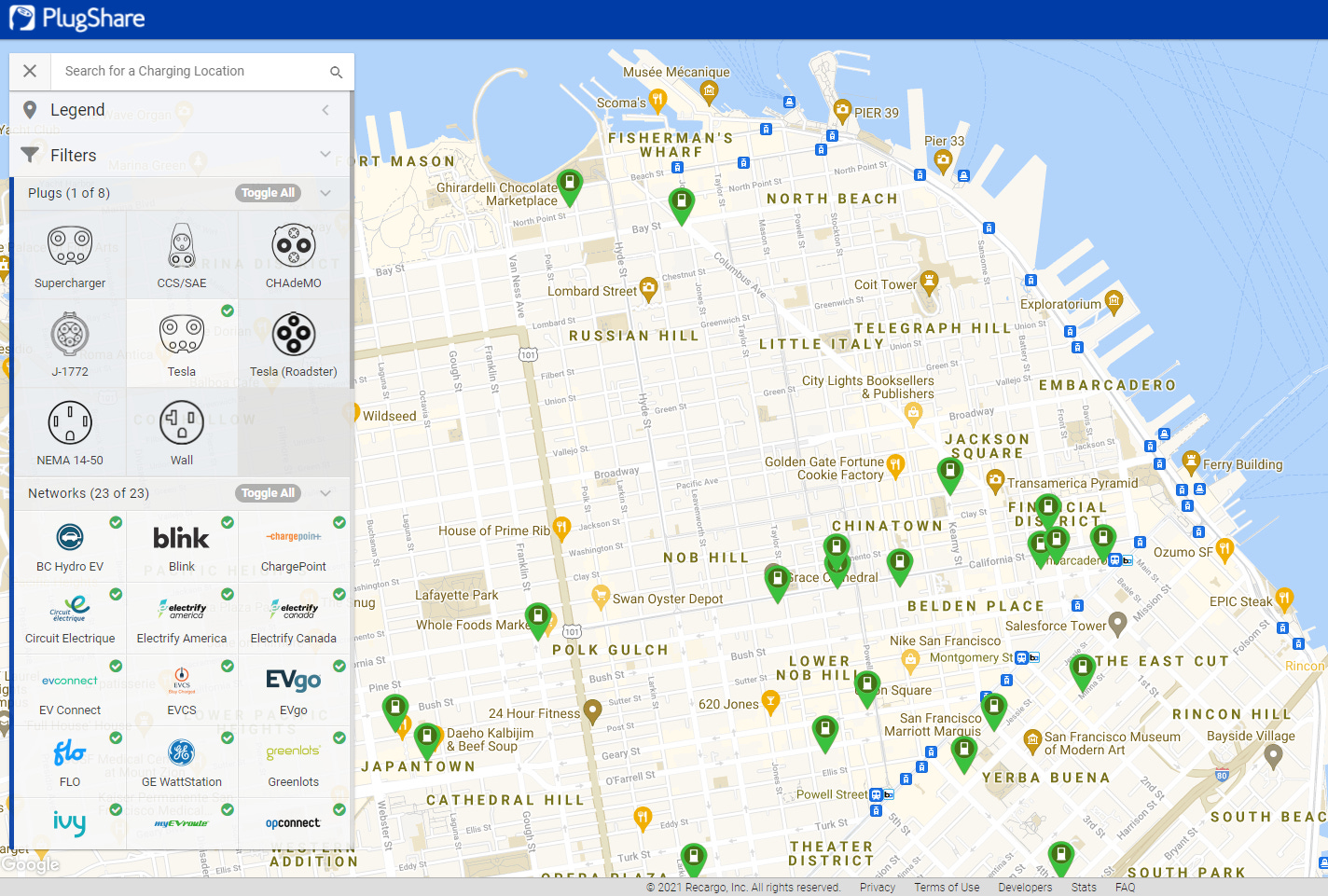

When you’re on the go, there are several ways in which you can find charging stations. The most straightforward is direct integration in the vehicle. For example, tapping a button on the Tesla’s console brings up several options for nearby Supercharger locations, or the ability to add a fueling stop along one’s driving route.

In-car integration exists to varying degrees in other vehicles but may not (yet) provide critical details like if stations are being used or in need of repair. Many drivers turn to the mobile apps of individual charging networks (e.g. Electrify America, Volta) for more details and to use integrated features like payments or loyalty programs. Searching within Google Maps directly is becoming increasingly popular, too.

A third-party app and website, Plugshare, has reigned as the preeminent catalog of charging stations across all public networks. Their mobile app has reportedly been downloaded by ~70% of EV drivers in the US and hosts an abundance of user-submitted station reviews, photos, and other data.

Just last week, charging network EVgo announced it had acquired the company that runs Plugshare — a move roughly analogous to Chipotle buying Yelp. From a business standpoint, the deal is a home run, notes VC investor and market commentator Reilly Brennan:

“This is one of those small acquisitions that everyone else in the industry must be slapping themselves about -- there's simply no way you could have that kind of access to 7 of 10 EV owners with such a tiny customer acquisition cost.”

EVgo has pledged that Plugshare will remain a neutral platform, a stance worth keeping an eye on by the driver community.